Executive summary

The final quarter of 2025 saw the planned engine rebuild pivot to invasive structural repairs before returning to course. While the “done-in-an-afternoon” welding tasks predictably expanded in scope, the engine rebuild has nonetheless proceeded ahead of schedule, bolstered by strategic outsourcing to professional machine shops. Agnetha is currently awaiting completion of the cylinder head renovations before final assembly and testing.

1. key performance indicators

| Odometer | 12345 km |

| Distance travelled this quarter | 0 km |

| Furthest distance from home | 0 km |

| Breakdowns | 0 |

2. engineering work

2.1. welding YUCK

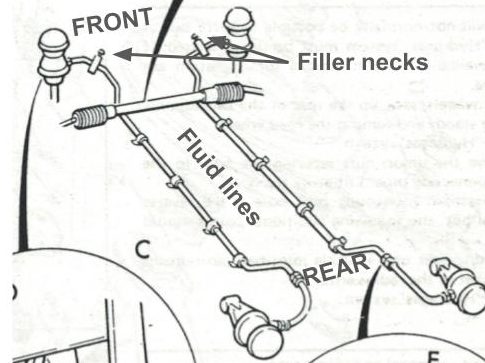

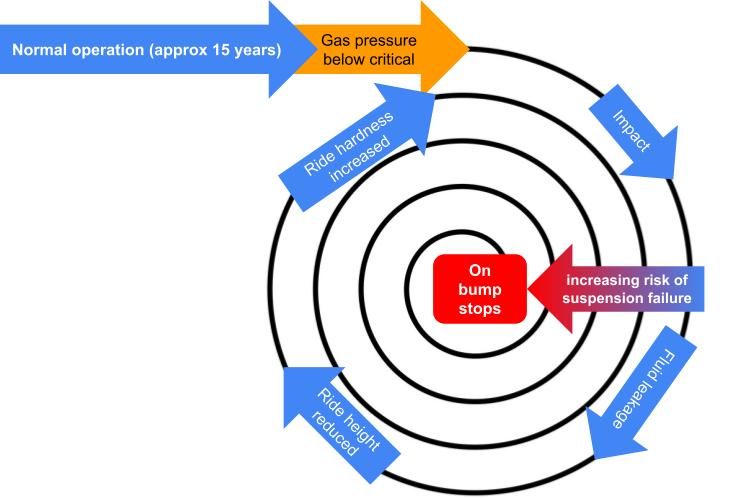

As is often the case, what started out as quick afternoon welding job soon turned into a painful ordeal lasting several weeks. I had noticed a small crack appearing near on the passenger side suspension tower around where the lower swing arm is mounted, and a hole above where the Hydragas sphere emerges from the tower. Half expecting both of them to be much worse than they seemed I was relieved to find the rust was only on the surface and neither the crack nor the hole extended very far when I wire-wheeled around them.

Having depressurised the suspension and removed the displacers I took the opportunity to remove what was left of the old bump stops and replace them with brand new stops. Then it was simply a case of welding the crack shut and welding the hole with the tiniest repair panel I’ve made so far – about 1.5 square centimeters!

Like an absolute mug I thought I’d got away with it so I decided to clean up the chassis rails, check for any rust and give them a fresh coat of Dinitrol. I had heard the rails were prone to rusting and I was about to discover why: Directly below the suspension towers, the rails are double-skinned. The two panels are pinch-welded together and there is a drain hole drilled through at the lowest point to prevent water collecting inbetween the skins, and this – of course – is where the trouble starts. The passenger side rail has corroded somewhat around the drain hole, in that there is some surface pitting and the skins have a chunky layer of corrosion products growing between them but, overall, it’s solid enough for the time being. Over on the driver’s side, which has always been worse in terms of rust, the corrosion was much more advanced and heading into the “structural rust” paradigm; it had to be repaired.

Even with the relative luxury of a QuickJack this was a pretty horrible experience. It’s about as difficult a job as it gets for welding especially for someone with literal hours of experience like me. But the only way to get better at welding is to keep trying and gain experience. So although I’m not particularly happy with the results, I know the rail is solid again and perhaps, just perhaps, I’m a little better at welding now.

2.2. ENGINE REBUILD

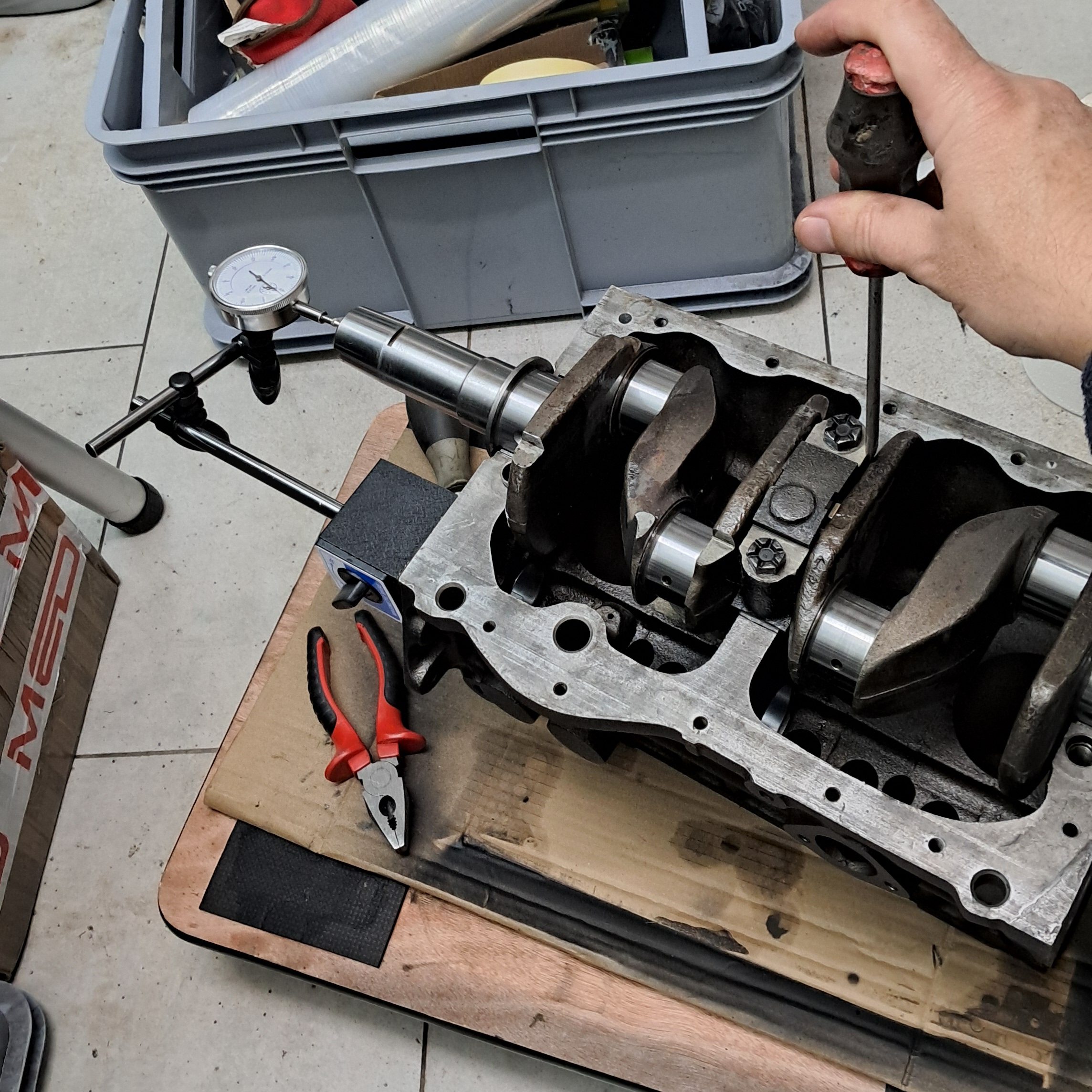

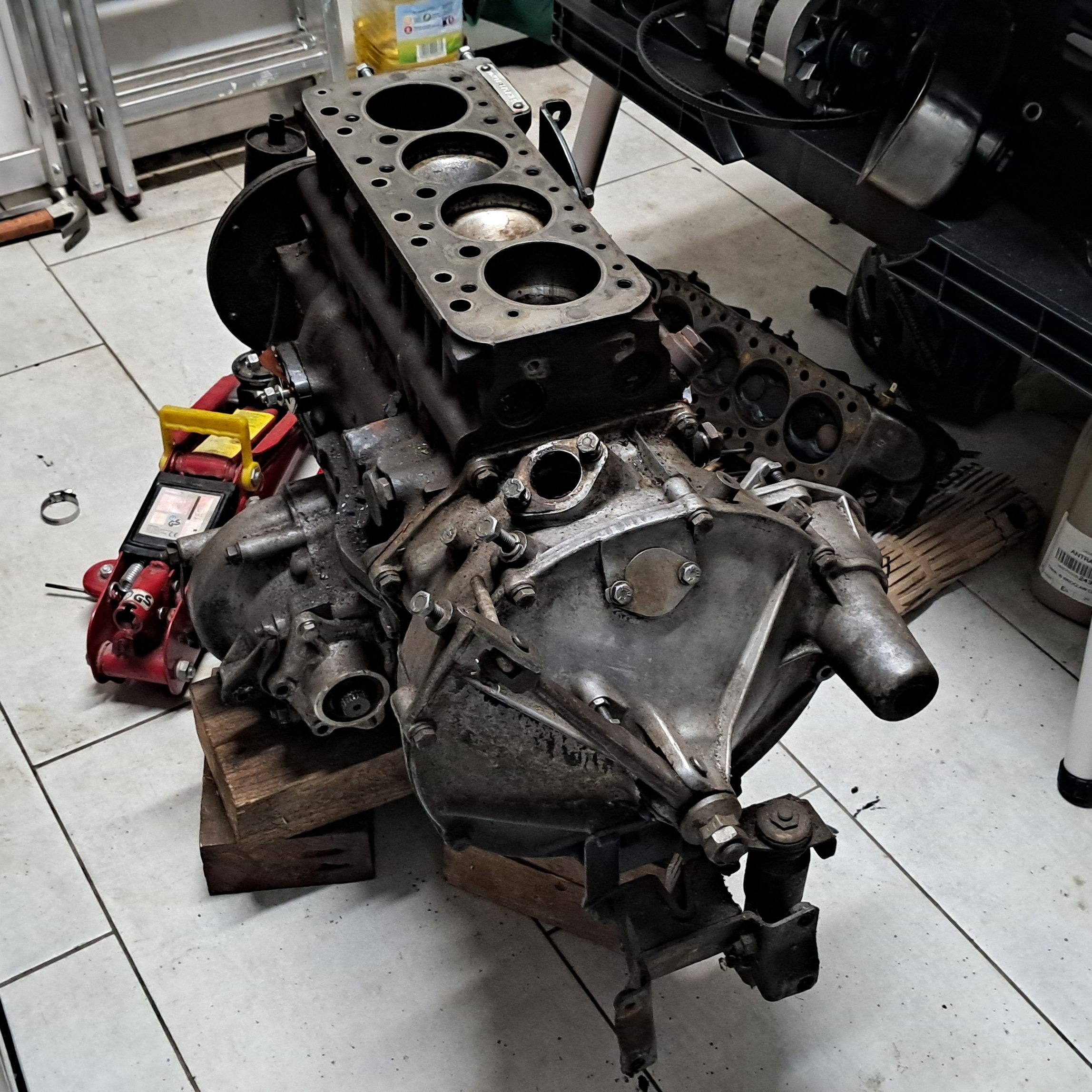

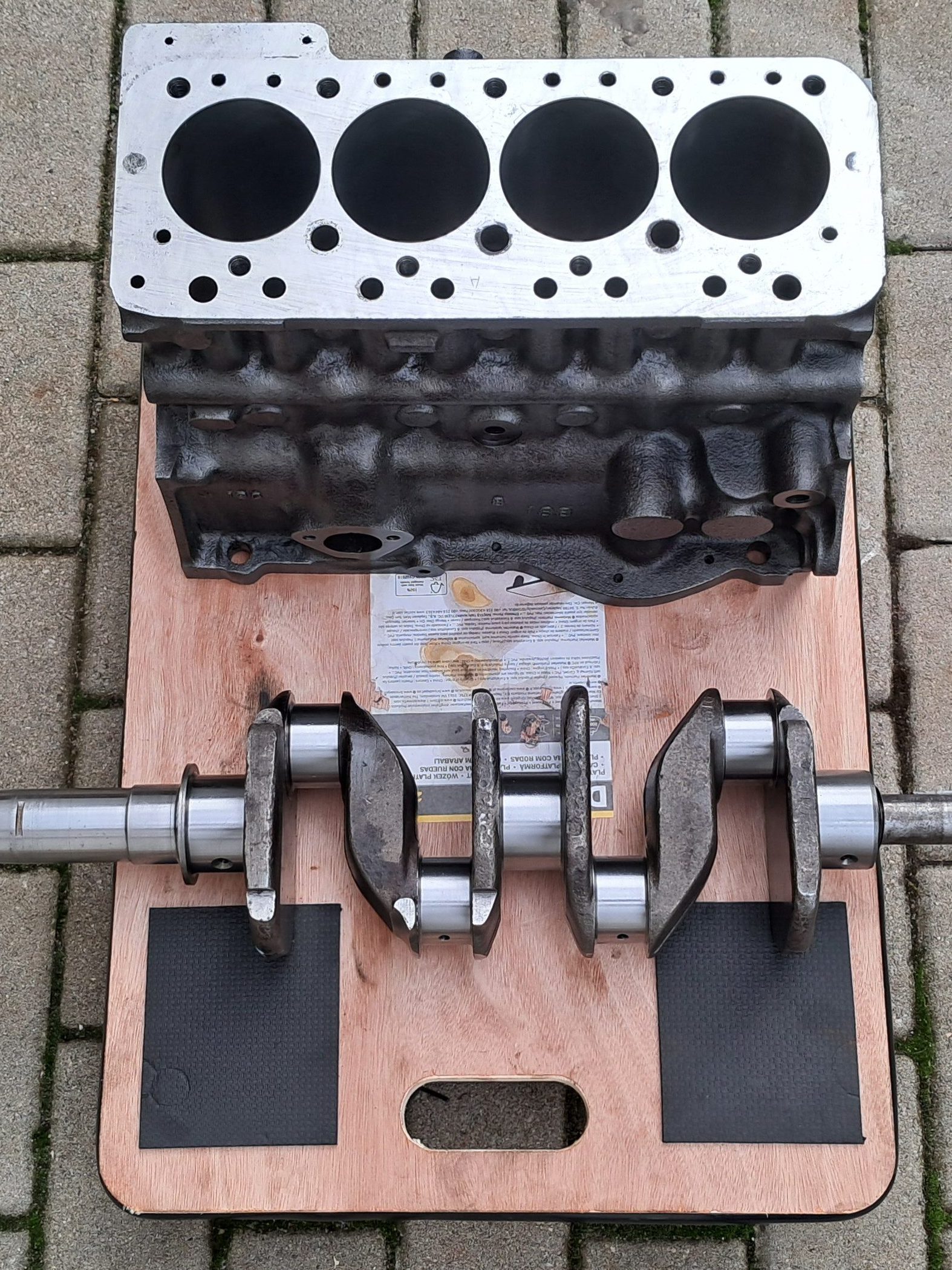

Having got all that horrible welding out of the way, returning to the engine was like putting on a warm pair of slippers. In the previous report Agnetha’s long-suffering A-series had been removed, deconstructed and the block sent to HT for assessment. As soon as the new pistons arrived from MED Race Technologies, and having given the block a damn good pressure-wash, HT got to work on the block and crankshaft. Within a week they had:

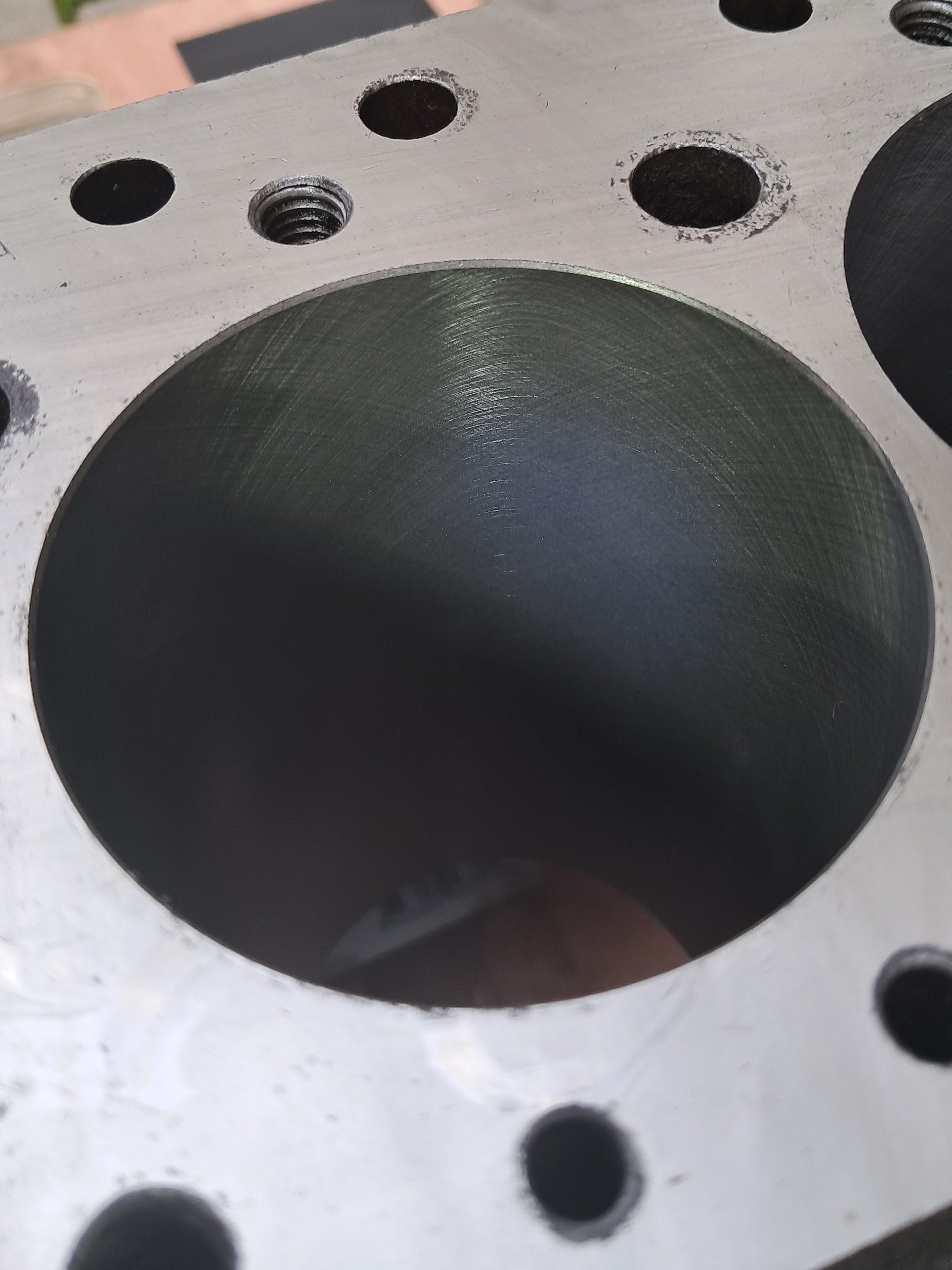

- Bored-out the block to 1311cc and honed the cylinders.

- Flattened and polished the top deck.

- Pressed in new camshaft liners.

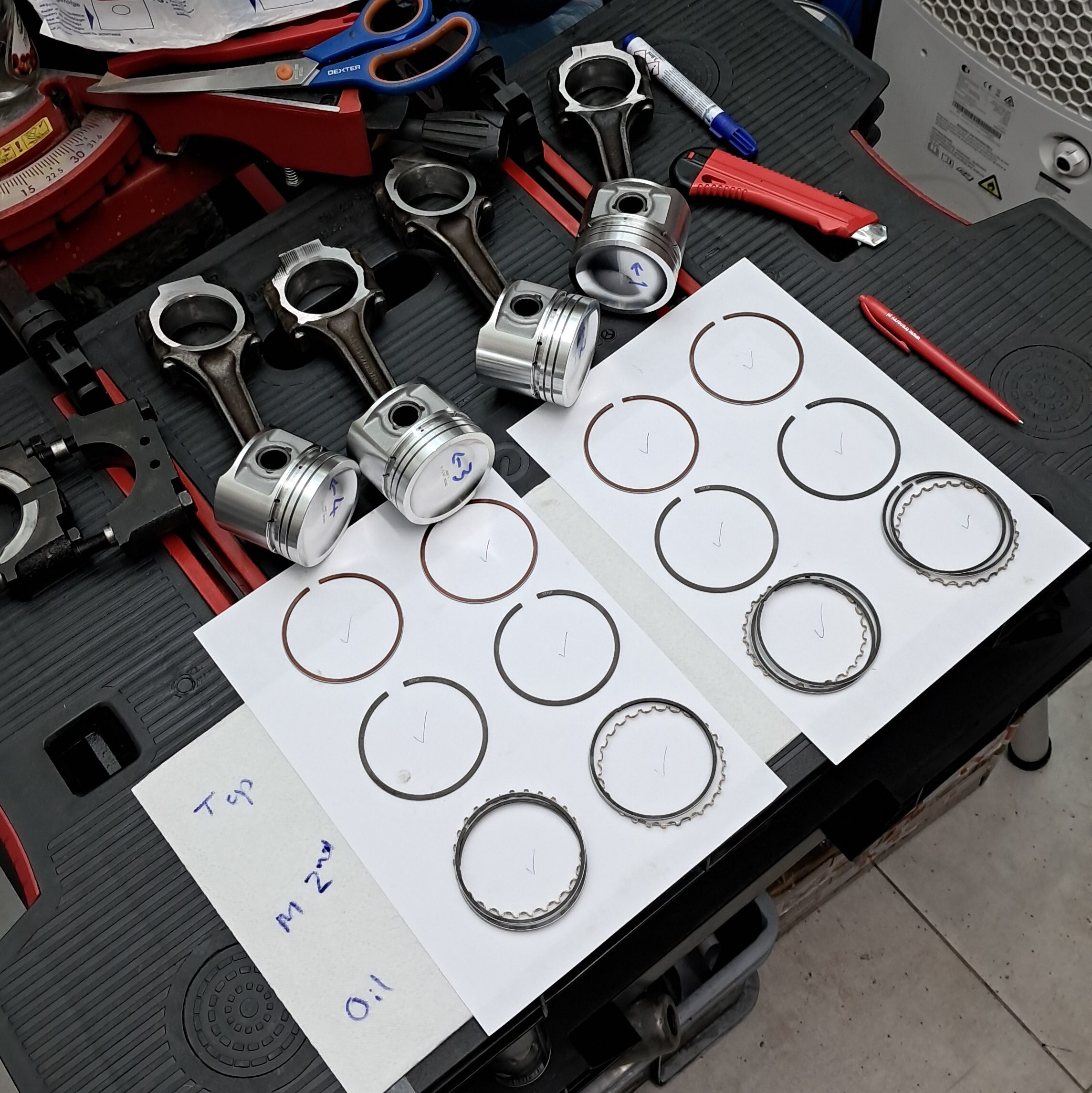

- Pressed the new pistons on to the conrods.

- Ground and polished the crankshaft to 20 thou.

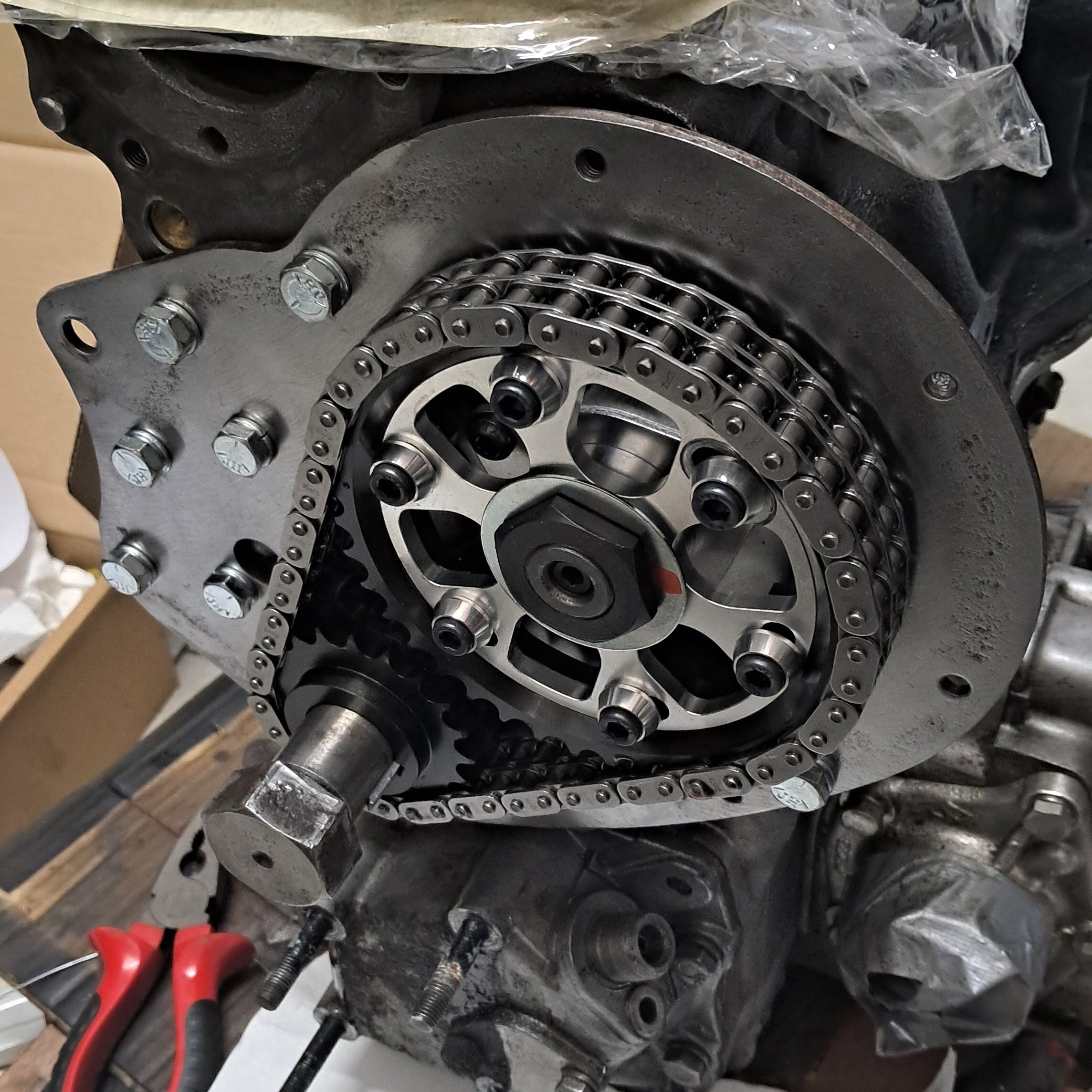

And all at a very competitive rate! Meanwhile I had taken delivery of some “sensible upgrades” from MED including the Stage 2 camshaft kit and, naughtiest of all, the Stage 1 ultralight flywheel and clutch kit. I’m not turning Agnetha into a sleeper but it would be fun to experiment a little with tuning so she can better keep up with traffic. These mods should enable a few tweaks here and there to her fuel economy and power delivery…and I imagine she’ll sound pretty mean, like half a Ferrari (or a 3rd if it’s a 12 cylinder Ferrari)

So now it was simply a case of putting the engine back together…how difficult can it be? In all honesty, not that difficult! The hard work is in the machining, since this requires an entire workshop and ideally 40 years of experience. Reassembly, it turns out, is just big Lego, some careful measurements and a bit of grunt every now and then. I found this YouTube playlist to follow along step-by-step and in the end I was very pleasantly surprised with how easily the engine fitted together (again, this is all down to the machine shop) and that everything was back to well within factory tolerances.

A small detail I picked up from the playlist was to gut and repack the flame traps. I imagine this is often overlooked. It’s a pretty gross job to remove the packing but once flushed out with WD40 it was straightforward to repack them with a pan scourer each – just make sure they’re steel pan scourers and not coated plastic!

Another detail that can, apparently, end in catastrophe if overlooked, was to replace the damper pulley on the crankshaft. Back in the later neolithic period, when a Mercian tribe lead by a druid monk name John Cooper realised the full potential of the BMC A-Series by building the first 1275cc engines, it was quickly discovered that the crankshaft has a tendency to ring like a church bell at about 5000 rpm and resonate the bottom end into a thousand broken pieces within a few seconds. Not ideal if you get caught out overtaking a ox-drawn cart laden with stone monoliths. To counter this, the crankshaft pulleys on 1275cc engines have a dual purpose: primarily to drive the water pump and alternator but just as importantly to prevent the dreaded 5 kHz resonance. To do this, the pulley itself is bonded by rubber to a steel wheel (the damper) so that any vibrations from the crankshaft are absorbed by the rubber and the damper, preventing the crankshaft from resonating.

The downside is that the rubber is known to perish after many years and, being deep in the engine bay, is difficult to inspect. Degraded dampers have been known to shatter and explode, taking the crankshaft, bearings and bonnet with it. So it’s a good idea to replace them every few decades. Unfortunately the S-pullies favoured by Mini enthusiasts do not fit the Allegro (I tried!) due to the engine mount immediately below the crankshaft fouling the outer edge of the balancer. This had me in a bit of a fix for a moment since I couldn’t find any Mini specialists that stocked the standard pulley, but thanks to a suggestion from Google Gemini I quickly realised that most MG specialists tend to stock them.

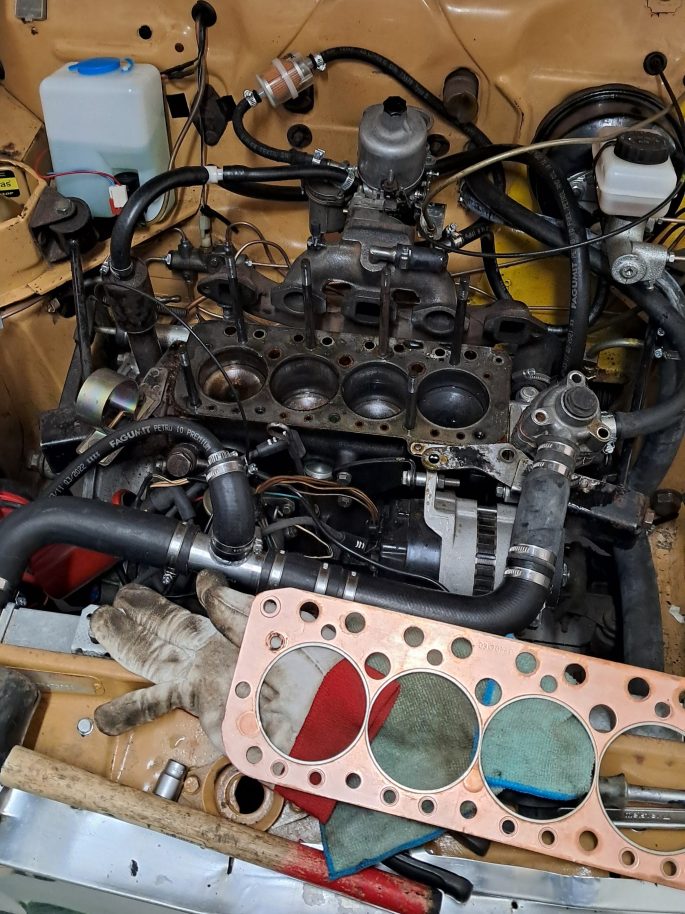

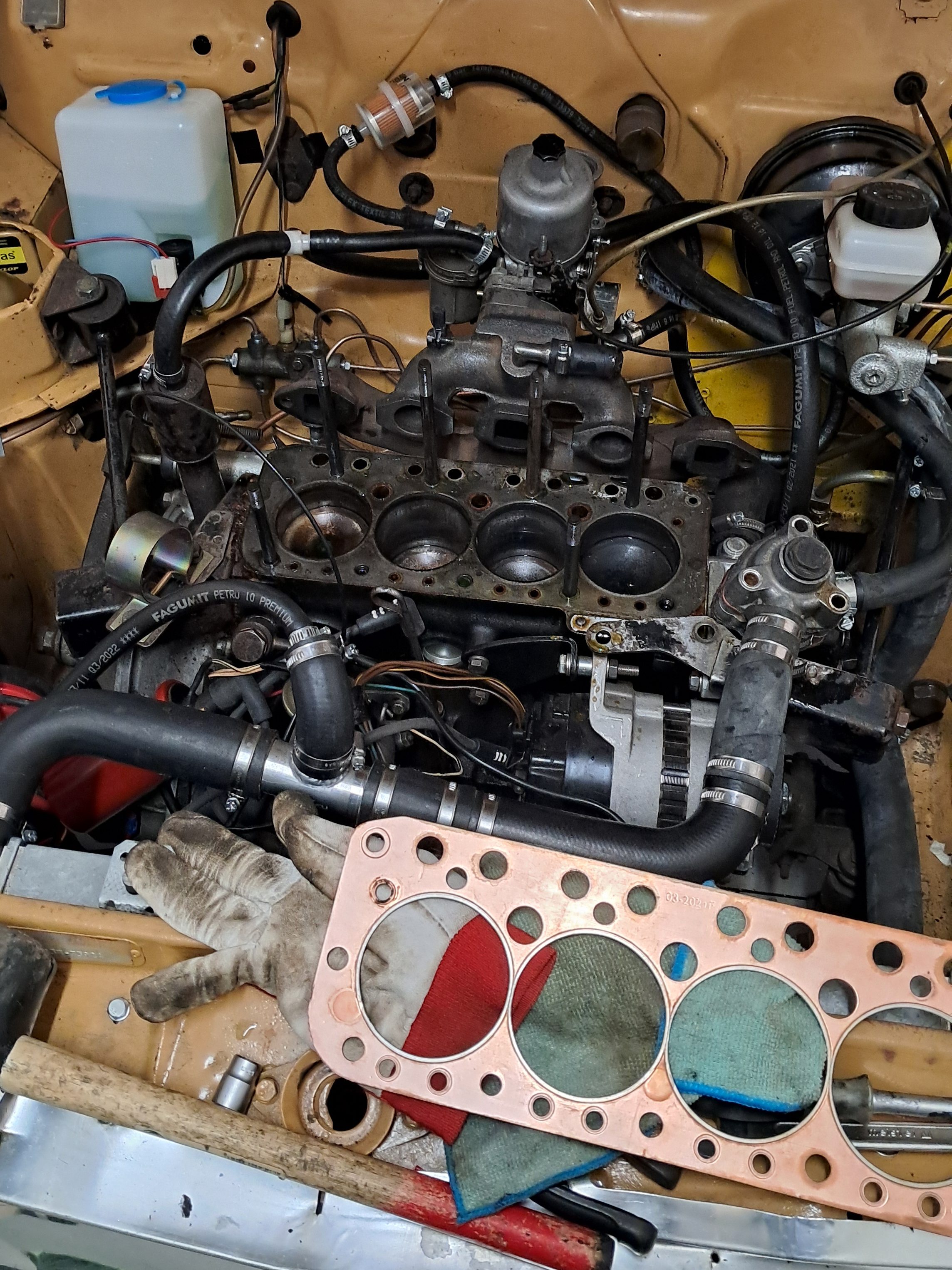

Finally, the cylinder head. I did a partial overhaul early in Agnetha’s recommissioning in 2023 with a general clean-out, new valves and new springs. However the valve seats were clearly in need of re-cutting and the exhaust seats were still the softer type for leaded fuel (it also looks like the exhaust seats were already beginning to melt!) With that in mind I’ve outsourced the head to another workshop for the full enchilada:

- Recut the inlet seats

- Install hardened seats for unleaded fuel

- Install new valve guides

- Lap new valves

- Flatten the deck

The head should return in January or possibly February as there is quite a lot of demand for this particular workshop, but I’ll take that as a good omen.

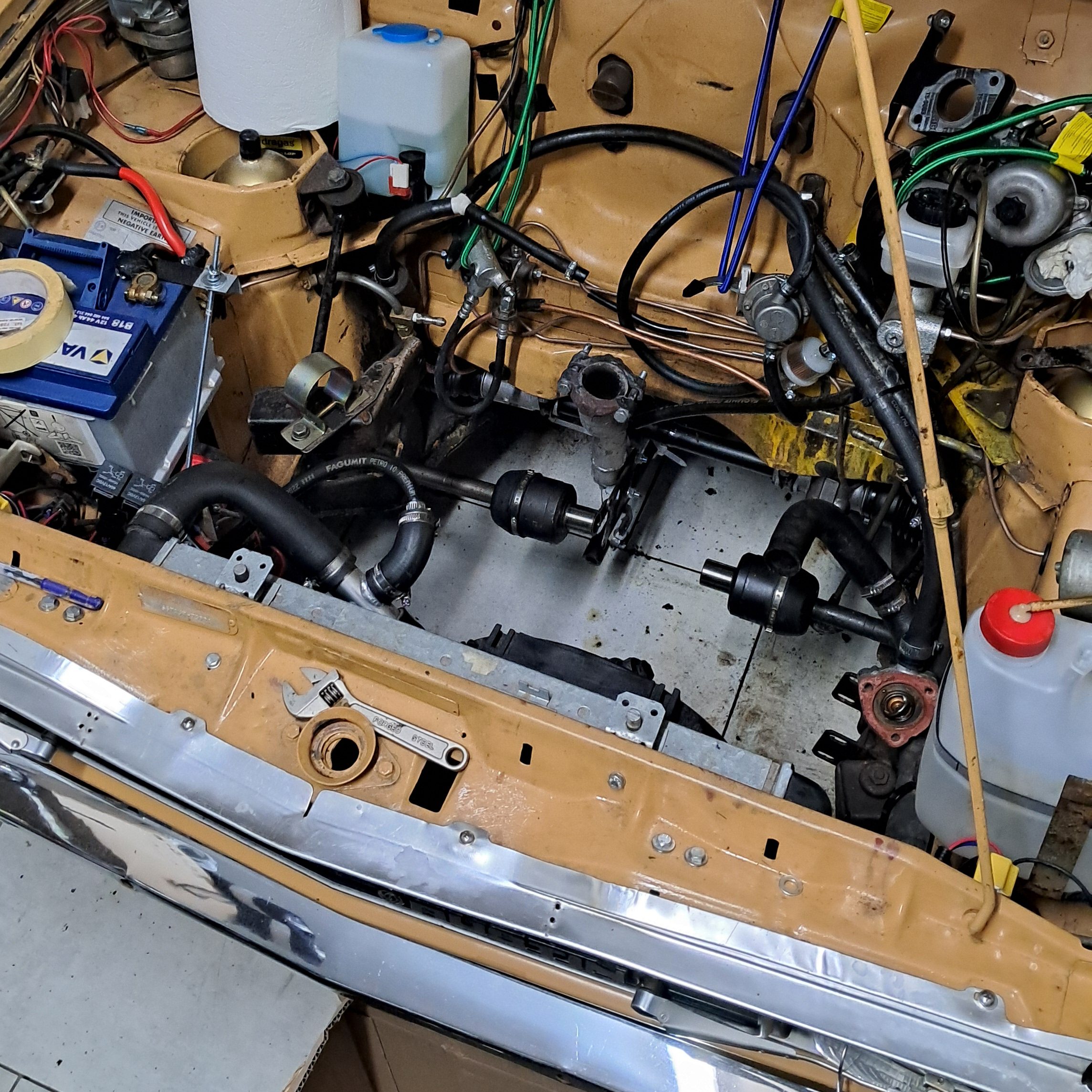

To make a bit of space, the final job on the engine for 2025 was to refit it in the bay with brand new bolts, since the original bolts looked like something from the Mary Rose.

2.3. CARB OVERHAUL

Another quick fix that turned into a battle lasting several days was to have a look at the carburettor to see what could be done about Agnetha’s fuel economy, or lack of it. I hadn’t calculated actual numbers for fuel consumption but it seemed “bus-like” and I wasn’t convinced that the thick carbon build-up on the spark plugs was due solely to oil fouling. Plus she was always very easy to start from cold which, for an A-series, all points to running heavily on the rich side. But it was during the early stages of the engine teardown, when I took the manifold off and half a cup of petrol fell out of the inlet and on to the floor, that I decided we had an over-fuelling problem and if I didn’t I solve that, it was going to make short work of my soon-to-be-rebuilt engine.

Once again vaguely recalling Agnetha’s recommissioning in 2023, I had rebuilt the carb but only got as far as replacing the throttle flap and the jet. For some reason the replacement fuel-bowl valve was still in a Mini Spares bag and I’d left the original, rather blunt needle in the carb. With the carb deconstructed on the bench I soon remembered why. The float didn’t want to be removed and, in those early days, I lacked the mechanical sympathy to know how hard I could hit anything seized in a shit quality, 50 year old aluminium casting, and what to do if something broke in the process – all I knew at that time was a new SU carb cost a lot more than the car was worth!

With a couple of years’ experience with calculated hammer usage built up since then, it was straightforward to remove the old float, replace the valve and swap the factory-fitted float for an ethanol-proof float that should easily outlive the rest of the car. The old valve was extremely worn and I’d put 10 quid on that alone being the root cause of the over-fuelling issue.

As for the needle, the absolutely useless aluminium retaining screw was seized. Despite a lot of soaking in WD40 and careful heating with a heat gun, I could not get it to shift and ended up shearing the head clean off. Lovely!

Eventually I had to drill out both the retaining screw and the needle. After some head-scratching and chin-stroking I replaced the utterly crap retaining screw with something more substantial: A helicoil and anodized steel grub screw that holds the needle perfectly in place and should come in very handy if I ever get into the mysterious world of needle tuning. And that’s it for the carb – but the only way to know if the fuelling problem is actually solved is to bung it on and fire it up.

3. outlook for next quarter

- Cylinder head

- Thoughts

- Prayers

- First start